CLANS AND

CHIEFTAINS

What follows are excerpts from an account of J. Swire‘s visit to the Sarajet e Kapidan Gjon Marka Gjonit in September of 1930. He, among many other notable figures of the 19th and early 20th centuries, had the privilege of being hosted at the Sarajet and experience first-hand the hospitality and warmth of the Kapedan and the people of Mirdita.

Down through the pines we went to the valley where an old woman ran from a house with a gift of cucumbers and words of welcome. Then, by a steep hot climb, we reached the house of Kapedan Gjon Marka Gjoni, Hereditary Chieftain of Mirdita and paramount chief of all the Catholic clans of Northern Albania. Gjon met us with solemn greetings as we scrambled over the last few yards of rough track. Like his house he is square-built and sturdy. Beneath a white skull cap his hair was close-cropped, his face bronzed. His dress was a collarless shirt, tweed coat and waistcoat and breeches, stockings, elastic-sided boots, and at his waist a dark red sash holding a tobacco box and a silver-mounted pistol from the King.

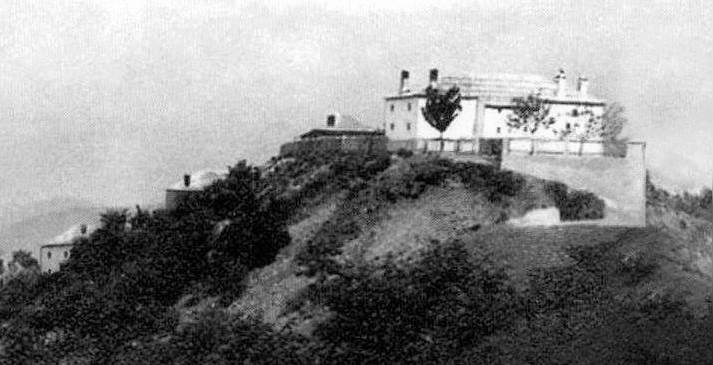

The house is of stone, whitewashed, with narrow iron-barred windows, standing enclosed by rough wooden palings 2,000 feet above the valley of the Fani-i-Vogel river. It was built in 1925, much in the style of a Scottish highland farm. By it are plots of maize and scrub but no big trees. Before it, beyond the valley, lie tumbled hills of light brown loam mottled with scrub and smudged, here and there, with sombre pine forests. Behind it the mountain goes up yet more steeply to the crags of Mali Shenjt (the Holy Mountain), so called because the famous Abbot of the Mirditi, Primo Doci, built on its summit a small wooden house and chapel for his use in summer. Behind those crags lies a wide grassy plateau, rich pasture, hemmed by great fir trees; and on the mountain’s eastern side are the tall forests and fertile plain of Lurja.

We sat under the arbour of oak branches for coffee while Gjon talked of himself, his land and his clansmen. He is Kapedan of nearly 20,000 Mirditi. He could raise 5,000 fighting men from his own clan in three days and as many more from neighboring clans within a week if the cause was popular.

The Mirditi were constantly at war, either against the Turks or with them against the Montenegrins. Though nominally under Turkey they paid no taxes and were independent in all but name. The founder of the present line of chieftains was one Marka Gjoni, who assumed the title and position of Kapedan in the 1700’s.

Mirdita remains a last stronghold of feudalism in Europe. “We pay no taxes” Gjon told me. “We never have, nor do we see why we should until the government is of use to us. We have supported ourselves for generations and can still do so. Nor will our men work on the roads. When the government builds roads in Mirdita we will labor on them, but we will not build other people’s roads for them.” No order by the Prefect could take effect without Gjon’s consent, and commune officials were chosen by the people and approved by Gjon. As there were no roads, only enough corn and other produce was grown for the clan’s needs and a margin for exports against very modest imports. In winter the flocks must go to the lowlands by Tirana and Lesh since Mirdita is under deep snow. There are many wolves, a few bears, ibex, chamois and wild goats.

Mirdita still abides by Lek Dukagjin’s laws which are modified at need by the official codes. “But the new laws only confuse us,” said Gjon. Of feuds there are almost none and they caused only four deaths in Mirdita in 1929. But only six weeks before our arrival Gjon had been nearly killed for blood himself. The cause of the trouble was the commonest one – an infant bethrothal. When the time came for the couple to marry, the girl would not have her man – from whose parents hers had doubtless taken her price long since; nor would she swear perpetual virginity which alone would free her. So she fled to Gjon, whose mother sheltered her until he could send her safely to Shkoder. The outraged bridegroom and his father scrambled down the mountain-side behind Gjon’s house and fired at Gjon through a window. But they missed and were chased away. A few days later they cut off Gjon’s water, then lay in ambush, but they were outwitted and overpowered. Such cases were difficult, because if a girl refused the man her parents had chosen and eloped with another, the man she went off with was held guilty of abduction; and for abduction a man was liable to imprisonment by the authorities and owed blood under the laws of the mountains too.

Our room in Gjon’s house was comfortable with tables, wooden chairs, one iron bedstead, carpets, a gramaphone (from the Italian Minister) and a big metal lamp hanging from a ceiling of stained boards. On the whitewashed walls were crude photographs of Gjon’s father and mother and other family groups, much like those in any English cottage. A big table was spread with a cloth and there were even table napkins! Gjon’s chief man attended us – a delightful character, a fair-haired highland Scot in type, who seemed to combine the functions of personal servant, Master of Ceremonies, and Privy Councillor. Over the collarless shirt he wore a coat and waistcoat a la Franka; but his baggy white linen trousers were like pijamas and his shirt tails hung from beneath a red sash at his waist. In the sash were a revolver and a silver tobacco box. He never stirred from the house without his rifle.

Gjon’s sons, lithe silent youths, waited upon us in true medieval fashion, directed by the Master of Ceremonies. The eldest Mark had married here only six weeks before with all the pageantry which has always characterized the wedding of the Kapedan of Mirdita’s heir. Stirling wrote in The Times his account of the event.

We slept comfortably, upon mattresses on the floor; and next morning there was an excellent breakfast of coffee and cakes. Then the Master of Ceremonies led us, by the precarious track which is the only way to and from Gjon’s house, to the old home of the Bib Dodas and Marka Gjonis not far away. Destroyed in 1921, part still lay in ruins; but Gjon had rebuilt the less ruinous part, a solid building of grey stone, and let it to the government as a boarding school. Then asked the government to enlarge it; but the government, who never did more for the mountaineers than they were obliged, pleaded poverty. “Unless they do enlarge it,” said Gjon, “I will enlarge it myself and put up the rent.” He equipped the school but the government paid the teachers. There were forty-three boarders and twenty-five day boys in five classes. A blackboard, a neat time-table and a row of cots seemed anomalies in this wild land!

Gjon’s was the only boarding school in all the northern mountains; and though education is nominally complulsory, not half the children go to school. Boarding schools in the mountains are urgently needed, but the mountaineers have been sadly neglected in favor of the influential landowners and townsmen. When the mountains lie in the iron grip of winter, covered deep by trackless snows and roamed by raveningn wolves, children cannot tramp miles each day to school. Nor can they go readily in summer, for communities are too widely scattered and distances too great.

Next day my three friends left me, returning to the capital under Abdulla’s guidance; and their places were taken by Major Oakley Hill (of the gendarmerie) who joined me here with his wife, his gendarme-orderly Ahmed, and a little qiraxhi1 (dubbed Tirana) who bounced and rebounded after his ponies like a piece of india-rubber and spoke in the sonorous nasal tones of the central Albanian lowlander.

J. Swire “King Zog’s Albania”, published Robert Hale and Company, 1937 – pages 99-111

1 horse-boy

You must be logged in to post a comment.