THE MIRDITE CLAN

Arthur (William) Moore (1880-1962), was a traveler and international journalist. In late 1904 Moore was employed as secretary to the Balkan Committee established to publicize the plight of Macedonian Christians. He travelled extensively in the Balkans, and in 1908 he reported on the Young Turk revolution for a number of British newspapers. While in Macedonia he became, in his own words, ‘the first west European to penetrate central Albania’. In late 1908 Moore was employed by a consortium of newspapers to report on the civil war in Persia. Arriving in Tabriz on 19 January 1909, he found himself trapped in a 100-day siege. In March he joined the constitutionalist cause, and on 19 April led the final sortie on royalist forces, which helped to alleviate pressure on the town until Russian relief forces arrived. He later returned to Albania for further travelling in 1914. While in Mirdita in 1908 he was a guest at the Sarajet. What follows is an excerpt of his account of the visit in Mirdite in 1908.

CHAPTER XXIV – THE MIRDITE CLAN

From Bourgayet I struck straight north, making for the heart of the Mirdite country. Mat is entirely Mohammedan; Mirdita is entirely Catholic. Between the two lies Kethela, which is mixed.

To the outward eye there is very little difference between Mohammedans and Christians. The Moslem women go unveiled and do not hide themselves from men. The Christian women wear veils for ceremony, like their Mohammedan sisters, and are in general no less in the background of the picture; they have also their own quarters in the house. The mosques have no minarets and, save for the absence of the Cross, are indistinguishable from the rustic churches. The blood feud rages everywhere, but between Albanians in the mountains there is no religious quarrel whatever.

I found a family living under one roof in Kethela in which some were Christians and some Mohammedans. The Catholics of Mirdita take Mohammedan wives from Mat, who dutifully accept the religion of their husbands. Polygamy is possible for the Mohammedans, but is rarely practiced, and the moral standard is high.

The feudal chiefs of Mirdita are called bajraktars, that is, bannermen, or kapedans (captains). There are five Kapedans in Mirdita, which has therefore five banners, to which the Mirdites gather for councils of war or peace. Jelal Bey has drunk of the blood of the son of the Kapedan at Orosh, which is the center of Mirdita, and the son has drunk Jelal’s blood. Consequently they are blood brothers, and the Mohammedan chief was in a position to pass me safely into the Christian country of Mirdita. He gave me two of his young retainers, who were to be my cards of introduction, and I set off at sunrise. For four hours we rode by cool and pleasant forest paths through Jelal’s estate, resting once at his chiflik, or farm-house. The two boys, Gjon and Ali, were great friends and in high spirits. At intervals they fired their Martinis in sheer glee, dexterously swinging these behind their backs and up under their left shoulder so that the bullets went whizzing upwards, past the ears of the Bey Effendi whom they delighted to honor with this inconvenient exhibition of their skill. Gjon is a Christian and lives in Kethela, so he took us all to lunch at his home. There are forty members in his family, which is not considered large.

In Kethela there are three kapedans with three banners. This was a new world, for Kethela had not yet accepted the Constitution. Consequently the blood feud was not yet checked, and men who had enemies hid themselves and walked with greater care than usual, fearing lest their foes would hasten to wreak their vengeance before the truce was made.

This was the very day of deliberation on the Constitution, and as we passed the open place of assembly the clans were already gathering. They pressed me to stay, but the meeting would not be till evening, so regretfully we pushed on to Gjon’s house. There, while we ate, a party of warriors dropped in from the wayside to share the open hospitality of the house, according to the custom of the country. “Are you brave?” was the greeting of the grizzled leader to me. Fortunately it is not necessary to answer this customary question except by direct tu quoque. Coffee was freshly roasted and served for all. We smoked in a semicircle, and fell to talking. The grizzled leader and his party were fresh from an exploit, and told us their story. The day before, with the view of forestalling the Constitution, a man had killed not his enemy, who was hiding himself, but his enemy’s friend whom he took unawares. The murderer had fled; so my new acquaintance and his friends had that morning burnt his house and all his goods, to their great satisfaction.

“Had he a wife and little children?” I asked.

“Yes.”

“What will become of them?”

“We shall do something for them; we shall take care of them,” he answered.

Weary with this hot morning’s work, the party was resting at Gjon’s house before going on its way to the meeting for the acceptance of the Constitution. It looked as if the Albanians were prepared to fight like devils for conciliation!

Of what the Constitution meant, and of the manner of its coming, they knew nothing. The head of Gjon’s family, an old Christian in the corner by the charcoal, crooned of the new liberty the Sultan had given. He called him “the king,” for the Albanians have their own word Mbret for king, or sultan. The younger men said the jemaat had done it themselves. “But how can it come without the king? There must be a king. It is he who has done it,” persisted the old man. The young men, Mohammedans for the most part, laughed at him. They understood that the jemaat could surround the king and tell him what he must do. But the old man could not understand how such a thing could be.

“Are you a consul ?” the leader asked me. “The consuls at Scutari disturb everything in this country. I think this Constitution is something you have made the king do.” More questions were fired at me. “Is it because they want us to go and fight some enemy that the Turks have made the Constitution?”

“Would you go?” I asked in return. He made no answer, and silence fell on the whole group.

“What will you do with all the rifles now?” I asked.

“If you live at peace amongst yourselves you will not need them any more.”

“Ah, we shall keep them to fight the Giaours,” he said quickly. By Giaours he meant non-Albanian Christians, for the Albanian Catholics are not reckoned Giaours.

“But why should you want to fight the Giaours? Are you not all to live as brothers now? I am a Giaour; are we not friends?”

“Ah, that is different. You are with us. You will speak for the Skipetari (Albanians). Let the Skipetari, the sons of the eagle, be free in their mountains.”

And with that the party rose, and bidding me a hearty tungjatjeta, Godspeed, went on its way to inaugurate the Constitution.

Gladly would I speak for the sons of the eagle had I the power. I realized that the Young Turks would have to walk warily if they were to tame these wildfowl of the mountains to the sober limits of the Constitution. What would happen when Mat and Kethela and Mirdita were asked to pay taxes I did not know. But on the whole I was glad that I was not the tax gatherer. The ancient Illyria meant the “land of the free”; and lirija to this day means “liberty” in the tongue of the Skipetari.

Gjon and Ali took the road again, and, after shots had been fired to celebrate the start, they burst into song. It was a song of Jelal Bey, and told how, six weeks before, a young man had carried off a girl from her parents and fled with her to the mountains. Thereupon Jelal Bey had sent pursuers, who had burnt his house and all that he had, thus avenging the parents and fulfilling the law of the mountains. We fell in with more company than usual, and should have fared ill without Gjon and Ali, but they were a sufficient passport. When friends meet they butt each other on each side of the forehead like calves, at the same time clasping hands. Gjon and Ali rubbed many foreheads that day, and after dark they brought me to the castle of Kapidan Marko at Orosh. Again I was received in patriarchal style, and this time my Homeric chieftain did not fail me. Kapedan Marko was away on a great errand, so Kapidan Ndue, his brother and the next in seniority in the famous Mirdite family, was my host; and Kapidan Ndue, like his retainers, was clad in the fashion of the sons of the eagle.

The trouble about travelling in Albania is the lavishness of the hospitality. I arrived nightly, late and tired and always an unexpected guest, but no mere hasty meal was considered sufficient to set before me. I had to wait three hours while a lamb was brought from distant fields, killed, and roasted whole; wheaten bread had to be cooked, for the maize bread in store was never thought good enough. There was also a soup, a pilaf, several made vegetable dishes, all excellent and better late than never. Grapes are eaten all through dinner, as though they were salted almonds.

Kapedan Ndue gave me a royal supper in his almost royal castle, while his own son and Marko’s son, who has drunk blood from Jelal Bey’s arm, acted as noble waiters. The center of the castle is in ruins, for the Turks destroyed it with artillery thirty years ago in the days of the famous Albanian League. Kapidan Ndue showed me the ruins, and explained the plans Mirdita was now forming to rebuild it for the exiled chief, Prenk Pasha, to whom the Young Turks had given permission to return. Time and again the Turks tried to destroy the rule of the kapedans and to establish their own governors; but always the new-comers were driven out. Once they sent a Bimbashi as Kaimakam, and Kapedan Ndue slew him with his own hand. For this a price was set upon his head, and for twenty-two years the kapedan had not been out of his own country nor taken the road to Scutari. Was it strange that men were weary of these wars and wanted to move once more in the face of their fellows, free from the shadow of death?

Mirdita is such a strange world to find in Europe that it deserves more than a passing notice. It covers a district which on the map is some thirty miles by twenty, but in reality its superficial area is greater. The northern portion is occupied by the mountains of Gajani and the Mundela range, which attain heights of 5,000 and 5,500 feet. In the East is the elevated plateau of Holy Mountain, some 4,200 to 4,700 feet high. South and West are an infinity of wooded heights, averaging 1,200 to 1,800 feet, and intersected by the valleys of the Greater and Lesser Fandis and innumerable smaller streams. The only level ground to be found anywhere is near the bottom of the river valleys, and the greater part of the whole area is forest-clad. Sandstone and granite are common, and there is limestone at Holy Mountain.

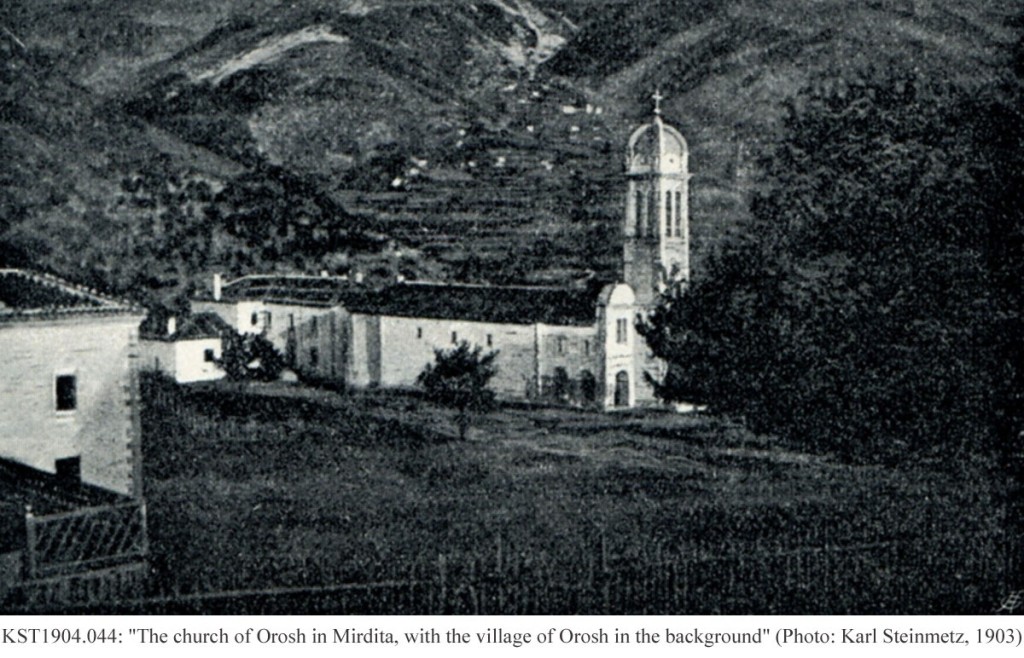

Mirdita owes the independence which it has so long preserved very largely to the fact that there are in general only two ways of entering it, for the way by which I came from Dibra is no way at all. It can be approached from Scutari, or from the sea, but both these ways lie for several hours through narrow gorges with steep sides. Except for punitive expeditions, Mirdita has been left alone ever since the first Turkish occupation in the second half of the fourteenth century. After the death of Skanderbeg in 1467 and the fall of the confederate chieftains in the following years, it seems that the family of Count Pal Ducagjini, who had ruled over the territory lying to the north of what is now Mirdita, took refuge in these mountains, possibly at the Benedictine Abbey of St. Alexander at no great distance from Orosh, which subsequently became the seat of government and chief village of Mirdita. The name Orosh is not improbably derived from the Slav word varosh, signifying “town,” inasmuch as it was the only collection of houses. At its most flourishing period, Orosh is said to have consisted of no less than one hundred houses, encircling the Sarajet, and situated so close to one another that “a rat could pass from one end of the town to the other without quitting the tops of the houses.” The legislation of the Dukagjini was the traditional Kanun of Lek Ducagjini, which to this day remains the only law recognized in North Albania, and had already been adopted by Skanderbeg and applied to the whole territory under his sway. In the absence, therefore, of any direct representative of their natural chief, Skanderbeg, the Mirdites readily accepted the dominion of the Dukagjini, whose descendants, according to tradition, have continued to govern to this day. Since the beginning of the eighteenth century the ruling family has been known as the “Dera Gion Markut”, that is, the dynasty of Gjon Mark.

The early Sultans seem to have left the Mirdites full liberty, the sole condition of this autonomy being that they should supply a fixed contingent of mercenaries in time of war. There is a tradition that Murad II, delighted by the prowess which the Mirdites had exhibited at the battle of Kosovo (1389), ordered a charter of privileges to be inscribed on a tablet of brass and presented to their chief, Kapedan Tenekia. Teneke is the Turkish for “sheet of metal,” and either this was the origin of the kapedan’s name, or the kapedan’s name was the origin of the tale. In 1690 Suleiman II granted the chiefs a present of a hundred horse-loads of maize, and the record of this is also said to have been inscribed on a tablet. This custom has persisted to the present day, and every year seventy horse-loads are given by the Sultan to the governor and thirty to the elders of the five clans. If the Sultan be recognized as the suzerain of the new Principality of Albania, which the Powers are creating, the custom may even survive that annus mirabilis 1913.

The accompanying genealogical table was compiled many years ago, when he was Vice-Consul at Scutari, by Mr. H. H. Lamb, now Consul-General at Salonika, and I am very greatly indebted to him for permission to use it and a great deal of other information on the subject of the Mirdites. From this it will be seen that a direct line was maintained in the ruling family from the seventeenth century to the death of Bib Doda Pasha in 1868. Prenk, his son, was then aged twelve, and the Porte appointed Bib’s cousin, Kapedan Gion, as chief, styling him Kaimakam. Prenk was sent to Stambul, ostensibly to be educated, but really as a hostage. During the war with Montenegro in 1875 and 1876 the Porte called upon the Mirdites to furnish their customary contingent, whereupon they demanded as a condition of compliance that Prenk should be sent back to them. In the autumn of 1876 he was sent back to Scutari with the titles of Pasha and Mutessarif of Mirdita, but his ambiguous conduct and his intrigues with the Prince of Montenegro resulted in two Turkish expeditions being sent against the Mirdites in the

following years, in the course of which the old Sarajet was devastated, as I have already described. There followed a period of disorder, and great impoverishment of the family. In 1878 Prenk made his peace with the Sultan, but in 1880 he was again taken to Stambul and subsequently banished to Anatolia. The English Government, mindful of the fact that his father, Bib Doda, had fought gallantly in the Crimean war, is said to have interceded for him, and he was allowed to return to Stambul some fifteen years ago. His cousin, Kapedan Kola, was appointed Kaimakam by the Sultan. He in turn was succeeded by another cousin, Marka Gjoni, the actual Governor at the period of my visit. But during the whole of the latter’s rule and up to the present day there have been constant disorders.

Administration is in the hands of the Bairaktari of the five clans; Oroshi, Kushneni, Spatchi, Fandi, and Dibri. Justice is administered in each clan by its own Elders called in Albanian Kreen or Piece who, like the Bairaktari or kapedans, hold their position by hereditary right; the nearest male relative acts for a minor. Capital sentence can only be pronounced by the captains, but is executed by the elders or by the representatives of the aggrieved party. When fines, which are generally in cattle, are imposed, the amount levied is divided between the captain and the

elders, the former taking half.

The whole tribe is said to contain over two thousand families, which, if we take an average, not a very high one for the country, of twelve in a family, gives a total of about twenty-five thousand persons. Their pursuits are chiefly pastoral as, although the soil is not unfertile and there is good water, which they convey for purposes of irrigation in a system of open wooden aqueducts, the hollowed halves of tree-trunks, there is insufficient cultivation. There is not enough grain for the whole year, though rye, barley, wheat, and, on the low ground, maize are grown. Charcoal is burnt, and in the undergrowth there is a shrub called “scodano” (sumach), the leaves of which are dried and pounded for export via Scutari to the tanneries of Trieste. Skins, sometimes the skin of a bear, wool, sheep, goats, pitch, resin, pinewood, and honey are brought by the Mirdites for barter to the bazaars of Scutari, Alessio, and Prisrend. It is a good fruit country, and the vine, white mulberry, the wild pear, and the cherry are all plentiful. There are oak forests at Dibra, but at a height of fifteen hundred feet pine replaces the oak. Fir, beech, plane, poplar, elm, and yew are all to be seen. Iron is plentiful; silver, lead, antimony, and copper are said to exist, and in more than one place I saw surface coal.

To Mirdita there are three allied bairaks, or banners; Selita, Kethela and Kansi. And Kethela again is divided into Upper and Lower Kethela and Perlab. These belong to Mat rather than to Mirdita, but the majority of the inhabitants are Catholic. And in 1858, when Said Bey Sogol of Mat was in open insurrection, they availed themselves of the opportunity to place themselves under the protection of Bib Doda Pasha. Administratively they are in the Kaza of Kruga, but actually they have, of course, been absolutely independent of the Turkish Government. Kethela is very near the border line between Mohammedanism and Christianity. Polygamy exists, and the priests have much less influence than in Mirdita, where they are a superior and highly respected class.

I paid a visit to the famous monastery of the Mirdites, which lies beyond the castle of Orosh and is the first halt on the road to Scutari. The abbot is a great power in the land and all men speak well of him. He has travelled both in England and America. The Catholics of Albania are allowed many privileges, and priests and abbots all wear moustaches, for in Albania no one is counted a man without a moustache. In the mountains there is also a kind of polygamy amongst the Catholics, for when a brother dies the survivor takes his wife, according to the Mosaic law.

The priests set their face against this custom, but they have not yet succeeded in stopping it.

From Orosh, with one of Kapedan Ndue’s retainers for my guide, I made a day’s journey to Kasanjeti. My host at Kasanjeti was an old man, the father of a priest, and at his door was a school where some instruction is attempted in the Albanian tongue. The old man’s sister is a nun, who mingled freely with us without a veil, and for the first time in Albania I was greeted by the lady of the house. Mirdita had not yet accepted the Constitution, and the proclamation was fixed for Sunday. Meantime the blood feud raged. The youngest grandchild of the house, much

petted by the nun, was a little boy, whose father had just been killed in the vendetta. We talked of the Constitution and of the forgiveness of trespasses. The nun was intelligent, but implacable. She saw the beauty of the general principle, but she utterly rejected its application to a particular case. “Why,” she asked, “should the murderer of this child’s father go free? We must kill him or one of his friends. It is our right to kill him.” So spoke the Christian nun, representing the conservative force of women. The only possible pitch for my tent was some three hundred yards from the house. “Lark ! (it is far)” they said, “and we have enemies.” But on reflection it was remembered that the turn to kill rested with my host, and I was voted safe.

My Kasanjeti host gave me a grandson as a guide, and with him I made the journey to Scutari. Two hours from the town we fell in with an Austrian monk on an ambling pad, with a native of the country for escort, and in this company we made the rest of our way. The monk spends his holidays in the mountains around Scutari, holds evening classes for the priests, speaks Albanian, and takes hundreds of photographs of the places he visits. He carried a powerful telescope, and while I was with him he made many stops, sometimes to gaze through his telescope, sometimes to take a photograph. The people of the country declare that he is a monk pour rire, and that the cowl conceals an Austrian political agent. What the truth may be I cannot tell. To me he seemed a gentle soul, strange and taciturn, a man not unfriendly, but one who weighed his words and had little store of talk. It may be that men wrong him, and that he seeks the service of his Master in the wild land of the Mirdites, where there is much room for that love which is the fulfilling of the law. We left him at the custom house at Scutari, a weird figure of mystery to which I have no clue.

“The Orient Express” by Arthur Moore, F.R.G.S., published by Constable & Company Ltd, London, 1914

You must be logged in to post a comment.